Wastewater, Biosolids Come Under PFAS Regulation

Newsletter Articles

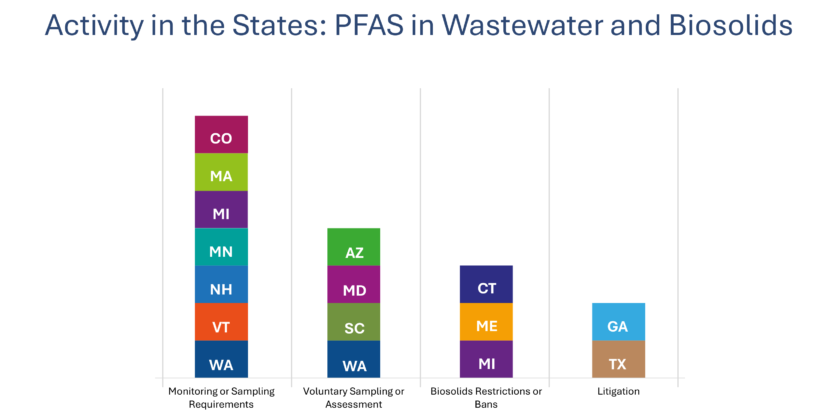

While initially focused on drinking water, public concern and regulatory attention has turned recently to PFAS in wastewater and biosolids. A New York Times investigation this past week[1] discussed potential threats to livestock and food safety from PFAS-containing biosolids used as fertilizer. Indeed, some states have already banned the sale and/or land application of biosolids containing PFAS, dramatically raising disposal costs for utilities that have relied on land applying wastewater sludge. Environmental groups have taken note and this year started to sue POTWs to force action.[2] More and more states have begun to require monitoring and to insert PFAS limits in NPDES permits. Questions are being raised as to the efficacy of treatment technologies[3] and the timing and feasibility of removing PFAS from upstream dischargers’ wastewater. Perhaps the only thing that is certain is that the issue is not going away. POTWs around the country, taking notes, are actively working to address these issues.

State regulation of biosolids

States have shown varying levels of concern over PFAS-contaminated biosolids. Some have attempted to address the issue while awaiting federal regulation. States are subject to federal regulations under 40 CFR Part 503[4] for biosolid use and disposal but retain the authority to make independent decisions about how to further manage biosolids while complying with federal rules. In the Clean Water Act (“CWA”) context, EPA has recommended state regulatory authorities begin including monitoring requirements in National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (“NPDES”) permits; EPA Region 1, covering Massachusetts and New Hampshire, has already finalized several permits requiring utilities to monitor and report on PFAS concentrations found in influent, effluent, and biosolids.[5] Similarly, Washington’s Department of Ecology (“DOE”) has issued a Water Quality permit for Seattle’s West Point Treatment Plant, effective June 1, 2024, that requires King County to monitor for PFAS in influent, treated wastewater, and biosolids the plant produces.[6] In January 2024, the Washington Pollution Control Hearing Board (“PCHB”) found that the state’s Department of Ecology General Permit for Biosolids Management violates the State Environmental Policy Act due in part to its lack of analysis of PFAS risks; until Ecology finalizes a new policy (which may take several years), POTWs are eligible for continuing coverage under the previous, now expired 2015 General Permit.[7] Such developments signal what we may reasonably expect in new POTW and other CWA permits across the country.

Newsletter Articles

Authors

Related Services and Industries

The following list summarizes relevant state action on the topic of biosolids monitoring and reporting:

- States actively regulating biosolids:

- Connecticut

- Bans the sale of biosolids and wastewater sludge containing PFAS.[8]

- Maine

- Prohibits land applying biosolids.[9]

- Michigan

- Since 2021, has required monitoring PFAS in all land-applied biosolids, and since 2017 it has prohibited applying biosolids deemed to be industrially impacted.[10]

- All Wastewater Treatment Plants (“WWTPs”) are required to sample for PFAS prior to land application. If PFOS is above 125 ppb, WWTPs are not allowed to apply biosolids to land without eliminating sources of the chemicals and implementing plans for pre-treatment to cut the concentrations. If PFOS is above 50 ppb, but less than 125 ppb, the application rate must be lowered to 1.5 dry tons or less.[11]

- Connecticut

- States requiring biosolids monitoring/sampling:

- Colorado

- Since 2023, biosolids sampling has been required either monthly or annually depending on biosolids amounts generated. The trigger level for source assessment and reporting is 50 ppb or greater.[12]

- Vermont

- In 2020, updated its Solid Waste Rules to require PFAS monitoring in biosolids produced in or imported to the state, as well as soils, groundwater and crops at land application sites.[13]

- New Hampshire

- Since 2019, has required all Sludge Quality Certificate biosolids to be monitored.[14]

- Minnesota

- Working on monitoring influent for PFAS at approximately 90 wastewater treatment facilities to help guide where source identification and reduction work should begin.[15]

- Massachusetts

- Since 2019, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection has required that residuals approved for land application (including biosolids and sludges from processing water treatment solids, paper sludge, and industrial sludge) be monitored for PFAS on a quarterly basis.[16]

- Colorado

- States monitoring/sampling biosolids on a voluntary basis:

- Arizona

- In June 2022, the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality performed a one-time voluntary screening of PFAS in biosolids that included 25 WWTPs receiving commercial and domestic water.[17]

- Maryland

- The Maryland Department of Environment is collecting PFAS sampling data for biosolids from selected treatment plants throughout the state. This initial data collection effort is being conducted on a voluntary basis, and results will inform the next steps in terms of any additional sampling or other actions.[18]

- South Carolina

- The South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control has requested that producers of municipal, domestic, and industrial sludge voluntarily sample for PFAS constituents in permit applications for land application of sludge.[19]

- Washington

- In April 2024, the Washington Department of Ecology conducted a one-time voluntary sampling event for approximately 45 WWTPs throughout the state. DOE will compile the data and publish a final report with its findings but does not plan to create any state-wide regulations on the subject until EPA has published its own guidance/rule. [20]

- Arizona

Only Maine has banned land applying biosolids, and it has been facing significant waste disposal problems as a result.[21] Other states addressing PFAS in wastewater and biosolids are generally focused on data gathering toward potential source control, while awaiting further guidance and/or direction from EPA or state legislatures.

Addressing PFAS in Biosolids at the Federal Level

Beginning in 2022, EPA has been collecting PFAS monitoring data from wastewater treatment plants, surface water, and fish tissue[22]. An EPA guidance memorandum issued in December 2022 serves as the basis for PFAS monitoring and pretreatment conditions required in state-issued NPDES permits.[23] EPA has announced that it will issue a PFAS land application risk assessment by the end of 2024[24] and analysis data that may reveal PFAS levels presenting a risk to communities surrounding POTWs.

To date, EPA has not issued any binding regulation related to PFAS in biosolids.[25] However, in a nonbinding “interim guidance,” last updated April 8, 2024, EPA recommends destruction and disposal methods for certain types of biosolids and residuals, including thermal destruction and landfilling.[26] In general, EPA has suggested that unless biosolids/residuals contain a “relatively high” amount of PFAS (a threshold EPA has yet to define), they may be disposed of at municipal landfills (as opposed to a hazardous waste landfill).[27] EPA issued this interim guidance since it is waiting to use the information from both its risk assessment (planned to be published by the end of 2024) and an Information Collect Request (“ICR”) planned to be published by the end of 2025 before it proposed federal regulations.[28]

Liability risks for POTWs with contaminated biosolids

As the PFAS regulatory landscape evolves, POTWs may be increasingly exposed to liability claims arising under federal and state environmental laws, including the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (“CERCLA”)[29], the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (“RCRA”)[30], the CWA[31], Safe Drinking Water Act, state hazardous waste cleanup and water quality statutes, and state tort law.

On April 19, EPA finalized its rule designating PFOA and PFOS as “hazardous substances” under CERCLA; the rule became effective on July 8.[32] The agency simultaneously issued a policy memo stating that it, “does not intend to pursue entities where equitable factors do not support seeking response actions or costs under CERCLA, including . . . publicly owned treatment works, municipal separate storm systems . . . and farms where biosolids are applied to land.”[33] That statement is not, however, binding on the agency, and has no effect on state or local government actions or third party lawsuits.[34] CERCLA also authorizes liable parties to file action against any entity that may share liability as a Potentially Responsible Party for PFAS-related clean-ups. Federal legislative efforts are underway to more formally protect wastewater systems from financial liability under CERCLA related to treating and disposing PFAS and PFAS-contaminated material, but the outcome remains uncertain. For example, the “Water Systems PFAS Liability Protection Act,” introduced in the Senate on May 3, aims to uphold CERCLA’s principle of ensuring polluters bear the cost of remediation without third parties such as wastewater systems getting caught in the crosshairs.[35]

PFAS has not been designated through RCRA or the CWA in the same manner as CERCLA, but both contain pathways for similar injunctive relief and recovery. There are also various defenses available under each federal statute. However, the success of either claim and applicable defenses will depend on specific court precedent, the facts of the matter, and any relevant permits or contracts held by the parties.

POTWs could also potentially be subject to claims related to PFAS-contaminated effluent based on state laws, including state environmental statutes, products liability, contribution from joint tortfeasors, nuisance, negligence, trespass, and breach of contract. Ultimate liability may depend on whether the state provides government immunity to POTWs and how broadly it applies.

Conclusion

The issue of PFAS-contaminated wastewater and biosolids has a potentially immense reach, implicating upstream and downstream entities involved in the municipal, industrial, and agricultural sectors. It is important that POTWs closely follow the developing regulatory and litigation landscape, assess liability risks, and respond proactively. For more information about Marten Law’s PFAS and biosolids practice, please contact Jeff Kray, James Tupper, or Emma Lautanen.

[1] Hiroko Tabuchi, Something’s Poisoning America’s Land. Farmers Fear ‘Forever’ Chemicals, New York Times (Aug. 31, 2024).

[2] Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief, Coosa River Basin Init. v. Calhoun, No. 4:24-cv-00068-WMR (N.D. Ga. Mar. 7, 2024).

[3] Miranda Willson, Can EPA’s PFAS crackdown spur new disposal methods?, E&E News (Sep. 5, 2024).

[4] Per the first requirement of CWA section 405(d) which requires EPA to establish requirements and management practices for the use and disposal of sewage sludge (biosolids).

[5] EPA, NPDES Permits and Through the Pretreatment Program and Monitoring Programs (Dec. 5, 2022).

[6] Department of Ecology, National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Waste Discharge Permit No. WA0029181 (issued Apr. 29, 2024).

[7] Nisqually Delta Ass’n v. Wash. State Dep’t of Ecology, PCHB No. 22-057 (Order on Motions for Summary Judgment, Jan. 29, 2024).

[8] “An Act Concerning the Use of PFAS in Certain Products”, SB 292, Gen. Assem. (2024).

[9] 38 MRSA §1306 (7)(A)(2).

[10] Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy, Land Application of Biosolids Containing PFAS: Interim Strategy (April 2022).

[11] Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy, Industrial Pretreatment Program (last visited Mar. 30, 2024).

[12] 5 CCR 1002-64.

[13] Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation, Solid Waste Management Rules (Oct. 31, 2020).

[14] New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services, Biosolids (last visited May 28, 2024).

[15] Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, PFAS Monitoring Plan (March 2022).

[16] Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, PFAS in Residuals (last visited Mar. 30, 2024).

[17] Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, Opportunity Statement: Evaluate Contaminant Fate and Transport in Biosolids (May 8, 2023).

[18] Maryland Department of the Environment and Maryland Department of Health, Maryland PFAS Action Plan (December 2023).

[19] South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control, Strategy to Assess the Impact of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances on Ambient Surface Waters in South Carolina (Apr. 30, 2021).

[20] Department of Ecology, Biosolids PFAS Sampling Study (Dec. 2023).

[21] The state-owned landfill where biosolids are disposed is on track to reach capacity by 2028, and lawmakers are currently considering significant investments to expand its capacity, Vivien Leigh, Time is running out to find new solutions to manage biosolids in Maine, News Center Maine (May 16, 2024).

[22] EPA, EPA’s PFAS Strategic Roadmap: Second Annual Progress Report(December 2023).

[23] EPA, NPDES Permits and Through the Pretreatment Program and Monitoring Programs (Dec. 5, 2022).

[24] EPA, Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Biosolids.

[25] On the industry-side of PFAS discharge regulations, the Office of Management and Budget recently received EPA’s proposed rule on PFAS-laden discharges from organic chemicals, plastics and synthetic fiber manufacturers. This is the latest step in the agency’s Effluent Guidelines Program Plan 15 (“Plan 15”), which includes analyses, studies, and rulemaking related to effluent limitations guidelines and pretreatment standards (“ELGs”). It is EPA’s vehicle to review, assess, and regulate industry discharges to waterways and into POTWs. Ellie Borst, White House launches review of PFAS wastewater proposal, E&E (Jun. 17, 2024); EPA, Effluent Guidelines Program Plan 15 (Jan. 2023).

[26] EPA, Interim Guidance on the Destruction and Disposal of Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Materials Containing Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances – Version 2 (Apr. 8, 2024).

[27] Id.

[28] David Tobias, team lead for EPA’s Biosolids Program, stated that the agency’s risk assessment values “will not be regulatory values,” and that a risk management assessment won’t be finalized until “at least a year after the risk assessment [is] completed”, PEER Sues EPA Over Failure to Identify, Regulate PFAS in Biosolids, Newsroom (Jun. 17, 2024).

[29] 42 U.S.C. § 9607.

[30] 42 U.S.C. §6901.

[31] 33 U.S.C. §1251.

[32] 7 CFR § 302 (2024).

[33] Memorandum from David M. Uhlmann to EPA Regional Administrators, Deputy Regional Administrators, Regional Counsels, and Deputy Regional Counsels (Apr. 19, 2024).

[34] 42 U.S.C. § 9606; 42 U.S.C. § 9659(a)(1).

[35] “Water Systems PFAS Liability Protection Act”, H.R. 7944, 118th Congress (2023-2024).

Authors

Related Services and Industries

Stay Informed

Sign up for our law and policy newsletter to receive email alerts and in-depth articles on recent developments and cutting-edge debates within our core practice areas.